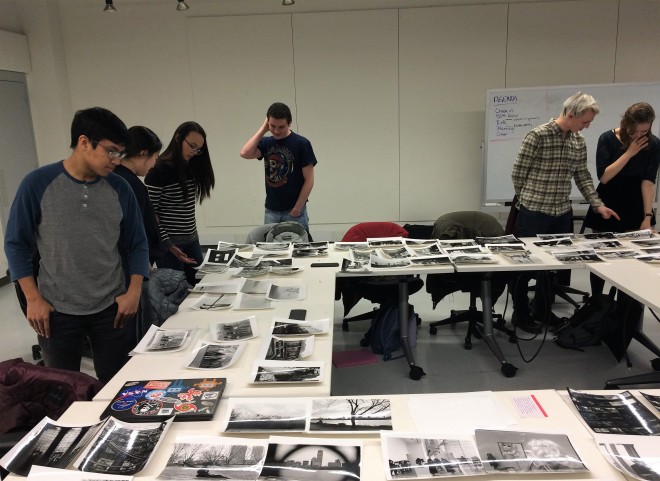

Through this piece, Barrett moves from discussing description as presentation of data to description as criticism/evaluation. In each component of description, Barrett shows how the critic adds a layer of interpretation and judgment to the description. Thus, description accomplishes the dual roles of conveying basic information about the artwork, as well as information about the critic’s opinion of the artwork. He also discussed formal elements, impact and effect of the medium, comparing style across multiples works/multiple artists, and using external information to add to the analysis.

One part of this piece that I particularly liked was the discussion of subject matter vs. subject. The examples Barrett picks out show how accurately describing the subject matter can require a more in-depth analysis of the contents of the image. Simply describing the elements of the image could give an incorrect impression of the photograph’s subject matter and the overall subject.

Another thing that caught my attention is how the context of the situation can be used in the evaluation of the image, and how critics differ in the extent to which they feel context should be used in evaluation. I tend to think it’s dangerous to read too much into images based on background information or ideas of the symbolism it contains — one of my mom’s artist friends used to comment on how he didn’t even know his art did all of the things that critics said it did. At the same time, I can also see how aspects of the photographer’s life can play into the photos he takes, and can be useful in interpreting his photographs.

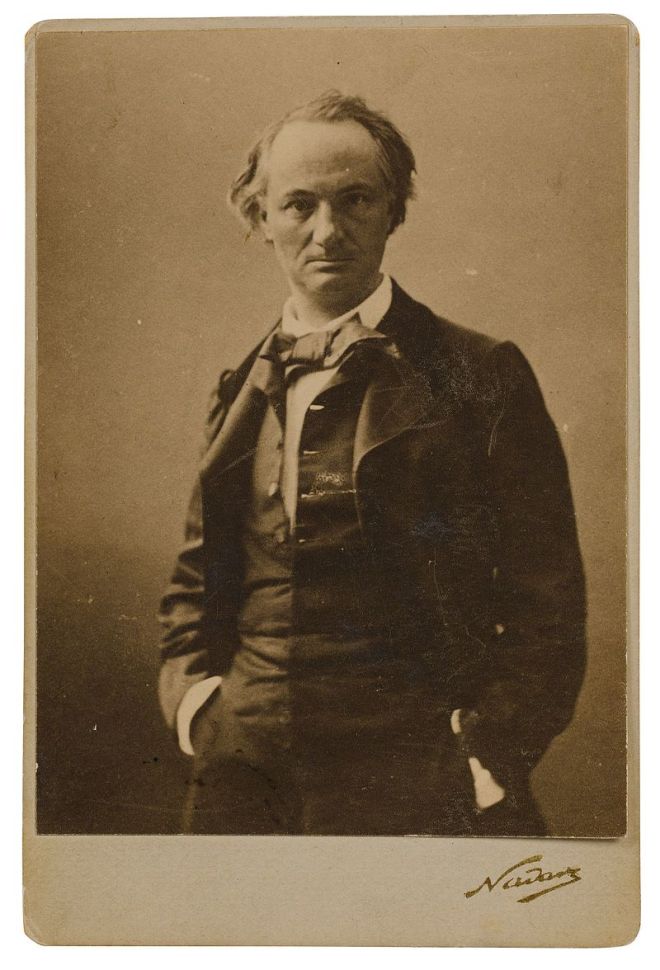

Baudelaire’s poems:

- Invitation to the Voyage: it felt almost like a lullaby or some kind of chant meant to lull you into blindly believing in the apparent beauty. I just pictured everything being covered in a soft, golden light, and mist rising from a river, and flowers and fragrances. Probably some angels singing. I think the beauty must be false though — there has to be something wrong, but I don’t know what it is. This reminded me of The Ones Who Walk Away from Olemas (by Ursula K. Le Guin).

- Correspondences: this one felt more ominous, even though the image sounded beautiful, perhaps because it was more solemn. I pictured monks in a forest.

- The Stranger: this reminded me of The Invisible Man (by H.G. Wells) for some reason. I felt like it was a man who had gone insane or was otherwise incapacitated and just didn’t have any connection to the world. He just spent all day staring up at the sky and watching the clouds go by, so that’s the only thing he could relate to.